In 1976, for a young, aspiring artist from Northern China, a crack appeared in everything and the light began to seep in. During the previous decade, the Cultural Revolution had imposed a communist orthodox hegemony. Mao had called on Chinese youth to purge “impure” elements from society and revive the revolutionary spirit. Not only was access to Western culture blocked, so was access to thousands of years of Chinese culture. It did not bode well for artistic freedom of expression. Then, Mao Zedong died. And, with his death, most of the final vestiges of the Cultural Revolution were discarded.

This was the political backdrop of Wanxin Zhang’s student days at Lu Xun Academy of Art. Possibilities for freedom of artistic expression were essentially non-existent just before he started his studies. Then, the rigid control began to crack. Catalogs from contemporary Western exhibitions began to circulate at Lu Xun. The light of possibilities began to brighten. In 1985, Robert Rauschenberg had an exhibit in China. Abstract expressionism had arrived. And, around the same time, Wanxin made a field trip with his school to the burial tomb of China’s first emperor Qin Shi Huang which had opened at Xiàn where 7500 terra cotta warriors and horses had been unearthed from four excavation pits. He made endless drawings. Two of the three key elements of vocabulary that would inform Wanxin’s art over the next 30 years were now in place. The terra cotta warriors provided the ostensible subject matter of his signature series of work: Pit # 5; and, abstract expressionism gave him the freedom to use the subject improvisationally to explore a broad range of cross-cultural observations.

essentially non-existent just before he started his studies. Then, the rigid control began to crack. Catalogs from contemporary Western exhibitions began to circulate at Lu Xun. The light of possibilities began to brighten. In 1985, Robert Rauschenberg had an exhibit in China. Abstract expressionism had arrived. And, around the same time, Wanxin made a field trip with his school to the burial tomb of China’s first emperor Qin Shi Huang which had opened at Xiàn where 7500 terra cotta warriors and horses had been unearthed from four excavation pits. He made endless drawings. Two of the three key elements of vocabulary that would inform Wanxin’s art over the next 30 years were now in place. The terra cotta warriors provided the ostensible subject matter of his signature series of work: Pit # 5; and, abstract expressionism gave him the freedom to use the subject improvisationally to explore a broad range of cross-cultural observations.

In 1992, after establishing himself as a successful artist in China, Wanxin got the opportunity to study in the MFA program at Academy of Art in San Francisco. Here the third element of vocabulary would fall into place. After completing his studies at Lu Xun, Wanxin started working in metal sculpture. However, in San Francisco, he had the opportunity to revisit his roots in clay. He was able to work briefly at the Foundry in Berkeley as an artist assistant to Peter Voulkous and he became acquainted with the work of Robert Arnesan. Both of these artists would greatly influence his subsequent work: the use of heavy slabs of clay, Voulkous; and the use of humor, Arnesan.

I recently interviewed Wanxin about his upcoming exhibition at Catharine Clark Gallery, Totem, and about his journey from his early student days in China to his home here in San Francisco. We talked about the defining events of our youth – for me the turmoil surrounding the Vietnam War in the late 60’s and early 70’s; for him, the collapse of the Cultural Revolution in the 70’s and the gradual opening of a window on the West. We also talked about cultural assumptions. We are all victims of propaganda. In Wanxin’s case, the propaganda in China during the Cultural Revolution was overt and ideas were rigidly controlled. In my case, growing up in New England, it was more subtle. I went to Japan in my early 20’s, and it soon became apparent to me that the things we “know” to be universally true are not. Many of the underlying assumptions that form our world view are culturally specific, not universal. In Wanxin’s journey to the United States, the culture shock was much more extreme. He started to question everything – something he continues to do with his art even now.

here in San Francisco. We talked about the defining events of our youth – for me the turmoil surrounding the Vietnam War in the late 60’s and early 70’s; for him, the collapse of the Cultural Revolution in the 70’s and the gradual opening of a window on the West. We also talked about cultural assumptions. We are all victims of propaganda. In Wanxin’s case, the propaganda in China during the Cultural Revolution was overt and ideas were rigidly controlled. In my case, growing up in New England, it was more subtle. I went to Japan in my early 20’s, and it soon became apparent to me that the things we “know” to be universally true are not. Many of the underlying assumptions that form our world view are culturally specific, not universal. In Wanxin’s journey to the United States, the culture shock was much more extreme. He started to question everything – something he continues to do with his art even now.

Wanxin noted that his work is about questions, not answers. In his signature series: Pit # 5, the terra cotta warriors are a surrogate for the Chinese subordination of the individual to the needs of society as whole. The addition of humorous, anachronistic elements to his versions of the warriors allows him to comment on society. One might make the assumption that he is criticizing the historical lack of individual freedom in China and lauding the individual freedom here in America. That would be a mistake. He noted in an earlier interview with Richard Whittaker in 2012: “Yes, there is great freedom here. The artist can do anything. The question is what?”. I imagine that there was a twinkle in his eye when he said that. Humor draws you into his work. It is easy access. Then, gradually it becomes disconcerting and it makes you question what you know.

Wanxin noted that his work is about questions, not answers. In his signature series: Pit # 5, the terra cotta warriors are a surrogate for the Chinese subordination of the individual to the needs of society as whole. The addition of humorous, anachronistic elements to his versions of the warriors allows him to comment on society. One might make the assumption that he is criticizing the historical lack of individual freedom in China and lauding the individual freedom here in America. That would be a mistake. He noted in an earlier interview with Richard Whittaker in 2012: “Yes, there is great freedom here. The artist can do anything. The question is what?”. I imagine that there was a twinkle in his eye when he said that. Humor draws you into his work. It is easy access. Then, gradually it becomes disconcerting and it makes you question what you know.

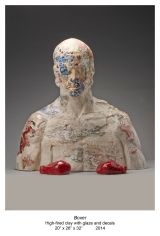

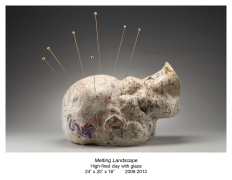

The current exhibition at Catharine Clark Gallery gives you a look at a broad range of Wanxin’s work. It is not just a continuation of the Pit #5 series. One gets a real sense of the importance of medium. I asked Wanxin about what drew him back to clay. It is the physicality of the medium. There is a direct, physical connection between the artist and the art. Emotions are directly transferred through the hands of the artist into the clay. If you could run your hands over the surface of one of his sculptures, the electricity would be palpable.

back to clay. It is the physicality of the medium. There is a direct, physical connection between the artist and the art. Emotions are directly transferred through the hands of the artist into the clay. If you could run your hands over the surface of one of his sculptures, the electricity would be palpable.

The exhibition itself is stunning. Catharine Clark has laid out her spacious gallery sparely. The lighting is beautiful. The works have room to breathe. I will focus here on just two of the works.

“Pink Warrior” is displayed together with some of Wanxin’s “Bricks”. It is an interesting juxtaposition by the gallerist. The bricks are strewn behind the pink figure. Each has a story of its own. Some are broken pieces of the Great Wall. Some are pieces of the wall with western graffiti. There is a price tag that comes with freedom. It is not all good. And, then there is the warrior, himself. The emotion is raw; the coloring incongruous. The calligraphy is deeply personal. Wanxin’s mother-in-law is a poet. When Wanxin first arrived in America and was struggling, he began to question whether he should be pursing art at all. Her poem reminds him how strong his voice his and how important his art is as a medium for that voice to be heard. It was a poem that allowed him to continue as an artist.

“Pink Warrior” is displayed together with some of Wanxin’s “Bricks”. It is an interesting juxtaposition by the gallerist. The bricks are strewn behind the pink figure. Each has a story of its own. Some are broken pieces of the Great Wall. Some are pieces of the wall with western graffiti. There is a price tag that comes with freedom. It is not all good. And, then there is the warrior, himself. The emotion is raw; the coloring incongruous. The calligraphy is deeply personal. Wanxin’s mother-in-law is a poet. When Wanxin first arrived in America and was struggling, he began to question whether he should be pursing art at all. Her poem reminds him how strong his voice his and how important his art is as a medium for that voice to be heard. It was a poem that allowed him to continue as an artist.

“Spring Whistling” is perhaps my favorite work in the exhibition. It has the basic elements that we have come to expect in Wanxin’s work: the traditional Chinese figure with its anachronistic Western sunglasses. Humorously, the crotch of the figure bulges inappropriately. It is a reference to a Chinese joke about what goes on under a monk’s robes. Then, there are also decals of traditional Chinese landscape and poetry that have been added to that surface in a third firing. And, the surface treatment of the sculpture itself is compelling on a purely abstract level. The raw, emotional treatment of the clay is undisguised. The work is not just about one thing. It does not have a single point of view. It is serious. It is humorous. It is anti-establishment. It celebrates cultural legacy. It is figurative. It is abstact. It is, for me, the best of what Wanxin has to offer.

a reference to a Chinese joke about what goes on under a monk’s robes. Then, there are also decals of traditional Chinese landscape and poetry that have been added to that surface in a third firing. And, the surface treatment of the sculpture itself is compelling on a purely abstract level. The raw, emotional treatment of the clay is undisguised. The work is not just about one thing. It does not have a single point of view. It is serious. It is humorous. It is anti-establishment. It celebrates cultural legacy. It is figurative. It is abstact. It is, for me, the best of what Wanxin has to offer.

Totem will be on display at through January 3rd, 2015. The opening reception is on Saturday, November 8th from 4-6pm.

248 Utah St.

San Francisco CA 94103

All exhibition photographs are courtesy of the gallery. Thanks to Leonard Cohen for the cracks allowing the light in.

Filed under: Artist Profile, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco Galleries, Wanxin Zhang | Leave a comment »